Game Information:

Name: Psychonauts

Released: April 19, 2005

Developer: Double Fine Productions

Rating: 8/10

Hardware Specifications:

Processor: AMD Phenom II X4 955 BE 3.2 Ghz

Video Card: Diamond AMD Radeon HD 4670

Memory: 4 Gigabytes DDR3 PC10666, 1333 MHz

Hard Drive: 2 TB Western Digital Caviar Green

System Specifications:

Distribution: Arch Linux

Kernel: Linux 3.9.2

Graphics Driver: R600 Gallium3D Driver

Desktop Environment: Xfce with compositing

I had first heard about Psychonauts as an industry curiosity mentioned in a series of student video lectures about the history and development of video gaming as an art form. Mentioned as a notable commercial flop for the industry, the lecturer nevertheless pointed it out as a model of good video game storytelling. While this of course did raise my somewhat peculiar interest, a brief glance suggested that it was one of those old console games that may never ever truly see the light of day again, trapped on their own particular hardware release as if it were some kind of digital purgatory. There were releases for some desktop computer platforms, but I did not hear anything good about these, with them appearing to be inferior ports compared to the original console releases.

When a few months later Pyschonauts made its first Linux début as part of Humble Indie Bundle 5 (2012), I was still somehow not all that surprised by its sudden arrival on our platform's fair shores, even though I was still quite pleased by the fact. Just like Prey (2006) and Trine (2009) before it, the game had seemingly been filed by me as just one of those titles that was destined to come to our platform at some point, for no other reason than that it somehow seemed innately wrong that we did not even have it yet. This was not due to any particular interest on my part, but due to some strange intuitive understanding of how the industry works which I have somehow managed pick up. Since then Psychonauts has had something of a rebirth, not just on Linux but on almost every other gaming platform as well.

Moving beyond my appropriately zany initial introduction to the game, Pyschonauts is an action adventure platforming game designed and imagined by Tim Schafer, one of those people who made a name for themselves late in the last century as one of the great emerging video game auteurs. Coming to prominence as part of the recently completely axed developer LucasArts, Schafer was eventually forced out after the mood of the management had swung away from making the original adventure game titles that they were most loved for to making completely franchised game titles which always came with an in-built audience. Schafer, like so many other video gaming auteurs of the time, then formed his own development studio and began work on what was to be his own personal magnus opus, Psychonauts.

For those of you who would, quite understandably, be somewhat confused by descriptors such as “action adventure platforming”, it basically describes a mess of genres mashed into one; Psychonauts features third-person action and combat sequences, adventure game puzzles and inventory quests, and a whole range of jumping and navigational puzzles involving three-dimensional platforming. Now, I might as well reveal one of my own personal biases here: I hate three-dimensional platforming. When it comes to first person jumping puzzles they always make me feel a bit leery, but when you mix them in with the third-person perspective there always seems to be hell to pay. You just can not properly gauge your surroundings when you are leaning over your game character's shoulder, making leaping about from place to place always seem like self-inflicted torture.

It is with the gameplay where Pyschonauts does unfortunately fall flat on its face way too often than for comfort; in fact the final Meat Circus levels may forever be linked to more game controllers or keyboards thrown into walls than any other campaign in gaming history. Conceptually, Psychonauts is very sound as both a game and a design. In practice, the design often shines brighter than the game does. The third-person platforming grates, the combat is a little too finicky, and the game has a rather unfortunate habit of making the player feel rather obtuse, expecting him or her to grasp one small hard to spot gameplay point as being intuitively obvious, especially with regards to the boss fights which always expect you to realize one very specific way of disarming your opponent in the heat of the moment. One can use the bacon object you are eventually supplied with to receive some hints, but that was sadly not a very palatable option when I first played.

Still, it was on the storyline and plotting that the game was sold to me, and on this I can think on much kinder. Certainly, setting the game inside a summer camp for psychics is an interesting move, and the device of going into and out of other peoples' minds allows for more fresh locales and locations than most games could ever even think of offering up. It is also a mechanic that perfectly fits into an interactive medium, allowing someone to explore each representation of a person's mental landscape at their own leisure, taking care to soak in every detail or instead opting to bash through blindly in search of their assigned objectives. Even within the confines of the static levels, players are given an almost unparalleled amount of freedom when it comes to exploration, and this helps explain why the game was granted so many accolades despite some well known annoyances with the actual game mechanics that it often employs.

Looking at it all with a critical eye though, I do have to admit that the actual game plotting is not all that exceptional, if still admittedly competent. The game's villain is obvious from the very first cutscene, hindering the game's attempt to build up suspense by hinting at lake monsters stealing children away, and the game offers up few surprises when it comes to the main plot. The game's characters always act just as you expect them to, and most of their motivations are never truly fleshed out. The goals of the villains are also never clearly stated, other than bog standard lines about their wish to take over the world. The biggest problem for me though was the botched resolution of the troubles hinted at in the main protagonist's backstory, with their subsequent resolution offering up no answers other than the fact that his surmises about his past and his father were wrong. It is never explained how they were wrong exactly, so I guess that just got forgot about somewhere along the way.

Speaking of the protagonist, players take control of a young boy rather groan inducingly named Razputin, who is never seen without his trademark aviator goggles and cap. His father works in the circus as an acrobat, and pressured his son to become one as well, with Raz believing that his father was trying to discourage his growing psychic abilities. He is also subject to a “gypsy curse” that prevents him from entering any deep water, with it being stated that he and all his family had been cursed to die in water. Raz eventually flees the circus and sneaks into Whispering Rock Psychic Summer Camp, intent on becoming a Psychonaut (a type of government agent that uses their mental powers to protect people from other psychics and the criminally insane) in the few days before his father comes to fetch him. He is voiced by Richard Steven Horvitz, a fairly well known voice actor but one whose work I happen to be rather unfamiliar with.

Throughout the course of the game he will interact with a variety of other characters, ranging from the other campers, the camp's three main Psychonaut councillors, several inmates of an insane asylum, various forms of Fred Cruller, a demented dentist, a genetically modified lungfish, and a talking turtle, not to mention the various machinations and characters dreamed up by most of these people's minds. Each is given a character and personality of their own, although not always with the same amount of success – I must admit that I never got interested in most of the other campers no matter how much the game tried, which admittedly did put me somewhat at a loss when it came to understanding the quips Raz makes upon collecting their brains later in the game.

Mental landscapes range from a city populated entirely by Lungfish with Raz stomping through as a Godzilla style monster, a twisted world bent in on itself full of hidden conspiracies and secret agents due to it being the product of a paranoid delusional, a neurotic actress's own mental stage that fully realizes Shakespeare's famous witticism, a full blown Risk (1957) type game featuring Napoleon, a painter's primarily Picasso inspired mind trip with a large additional smattering of Dogs Playing Poker (1903), as well as the aforementioned Meat Circus, an infusion of Razputin's circus background and Coach Oleander's childhood past. One can tell simply from how much detail one has to put into describing these places that they are the obvious highlights of the game. Of these, the obvious stand outs are the conspiracy theorist's mind, the fully acted out table top war game, and of course Lungfishopolis, primarily as these allow for the greatest amounts of fun interaction with the game environment.

In Lungfishopolis, one is given free reign to smash and rampage through a large urban metropolis. In the Milkman Conspiracy, one has to find and use several household objects in order to get past government agents pretending to be practitioners of several mundane everyday occupations. In Waterloo World one gets to go from being a piece of the game board to moving other pieces in order to strategically defeat a mental apparition of Napoleon. As previously mentioned, the amount of interactivity and exploration offered by these and the other levels is more than impressive, and it is this as well as the unique setups which has cemented Psychonauts as being a modern classic. To fully relate this to you, I will tell you the moment that finally sold me on it being an exceptional game.

One of the missions inside the Milkman Conspiracy involves playing the role of an assassin in order to get past a bunch of other agents playing assassins. Raz is provided with a fake rifle, something he is not very pleased about, commenting on it being fake whenever one presses the use key when the rifle is in his hand. As I was passing by the other would-be assassins, I happened to casually press the use key, with Razputin bemoaning his fake rifle to me once again. Upon saying this, one of the agents tersely replied “don't broadcast that fact. They look real.” It is one of those small touches one would not normally expect from such a game, and Psychonauts is full of them. Scattered throughout the game are small little additions to reward players for exploring, finding creative uses for their mental powers, or just plain messing around. The game also offers up a lot of opportunities for mischief, and one is never actually punished for their actions no matter how cruel or sadistic they may be, especially when they involve lighting fires.

Using Raz's Clairvoyance physic power, one can take a quick glance into people's minds and see what they see, often with hilarious results. Exploring inside Counsellor Milla Bordello's self-constructed Dance Party training world will reveal a secret room that shows one of her shocking repressed memories. If one returns to Waterloo World through use of the Collective Subconscious, Razputin will take offence at a group of cows casually grazing on top of the fields that he had previously commanded men to battle for, saying the immortal words “shame on you ungrateful cow”. If one goes back to Black Veveltopia, one actually does gets to see Edger Teglee playing poker with the dogs. The Collective Subconscious, by the way, is one of the better gameplay ideas put into the game, because it allows Razputin to revisit all of the minds he has touched thus far, at least until the last few missions where he does get cut off from everyone else's minds. There are also special bug creatures placed in people's minds that allow easy travel in and around them, and Ford Cruller installed an underground transit system under the camp that Rasputin can use to easily go from place to place inside the real world and fully flesh out the game's hub system.

Razputin is allowed eight distinct physic powers throughout the course of the game, with each represented by its own Psychonaut Merit Badge: Marksmanship, Levitation, Shield, Pyrokinesis, Telekinesis, Clairvoyance, and Confusion. Each one of these powers offers something new to the game dynamic. Marksmanship allows one to psi blast, what amounts to the game's main form of ranged combat, offering an alternative to basic melee based attacks. Levitation allows for the player to ride on a large ball of physic energy that can also allow Raz to jump and glide through the air, as well as adding a bit more kick to certain melee attacks. Shield creates a temporary physic barrier that protects Raz from both physical and mental threats. Pyrokinesis is exactly what it sounds like; with it you can light things on fire. Both Telekinesis, which allows you to pick up objects by using mental focus, and Clairvoyance, which I described earlier, can also be vital to solving many of the game's puzzles.

Confusion is the odd one out, as it comes in the form of grenades which you can chuck at opponents and other characters to temporarily daze and disorient them. Interestingly, most of these powers will work on objects and characters even when one is not supposed to have them yet and acquires them through cheating. All other items either need to be picked up as part of an active game mission or can be purchased at the camp store in the main lodge in exchange for psitanium arrowheads which are buried all around the camp. Arrowheads that are buried near the surface can be seen due to a blue glow emanating from the ground, and can be picked up by using the use key; deeper arrowheads can be collected in larger numbers by buying a dowsing rod from the camp store. Mental arrowheads can also be collected in great numbers by bashing up otherwise unimportant objects in people's minds, alongside other power-ups.

Other items include dream fluffs, special candies that can restore Razputin's health, a cobweb duster, an ultimately necessary item needed to clear away a person's mental cobwebs whilst one is in their minds, and a mental magnet, which attracts mental heath, energy, and confusion power-ups to the player while he is in someone's mind. There is also a fairly useless novelty item that allows the player to change the colour of their Levitation bubble. I strongly recommend investing in these items fairly early in the game, as they make progressing through the main campaign much, much easier. Dream fluffs come in especially useful since they will automatically be activated when Razputin's health gets low, and the mental magnet will end a lot of wasted time chasing after bouncing power-ups, and also help to prevent them from falling out of reach.

Every time you enter someone's brain you will also be given the option to collect mental figments, which are colourful outlines of people or objects that the person whose mind you are visiting is, ostensibly, imagining at the time. Scattered throughout their minds are also a series of boxes, bags, and trunks meant to represent a person's emotional baggage, which can be sorted by reuniting a bag with its tag, which can also be found scattered about their mental landscape. Spread about people's minds are also little mental vaults which Razputin can break into that often reveal some backstory point in the form of a mental slide-show. Collecting figments, sorting emotional baggage, and clearing mental cobwebs also come with distinct rewards, such as unlocking special primal memories which include things such as game concept art and other details. One can endeavour to collect all of these while doing the mission or afterwards by visiting it again through the use of the Collective Subconscious. Early on Razputin is also given a scavenger hunt list containing objects he can find in and around the camp, adding an additional element to help optionally prolong the game.

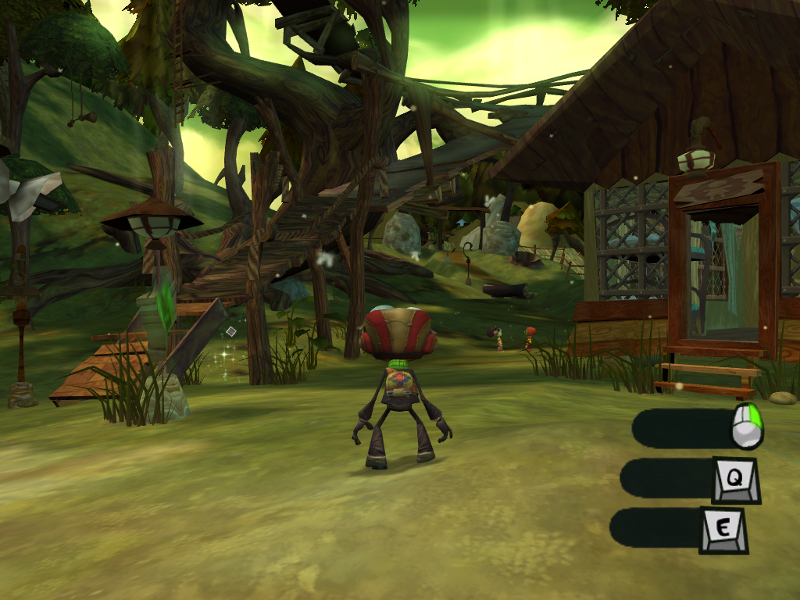

The games graphics are highly stylized, seeming very much in the style of the films of Tim Burton, something which does well to hide the fact the game's graphics were a little out of date even at the time of its initial release. The sound effects and voice acting are also very over the top, something that aids the surreal tone while at the same time taking the edge off some of the game's darker themes of mental breakdown, depression, repression, and primal fear, which if presented straight could often seem far more horrific than they actually do in-game. A more realistic air could have also actually hampered the game's suspension of disbelief, with the entire concept depending on a rather suspect if still enjoyable pretext of psychics playing around with real world representations of people's minds. It would have also made the game much, much less funny.

Enemies consist primarily of censors, people in blue suits with large stamps generated by people's mind to go after foreign intrusions. These come in a variety of sizes and shapes. Other enemies include various animals which the camp's large deposit of psitantium has endowed with physic abilities. These are probably the most annoying opponents offered up by the game, not just due to their psychic abilities but also due to the fact they are mostly detached from the main missions and mostly serve to act as simple annoyances as one is exploring either the camp or the nearby insane asylum. There are also several mind specific opponents and obstacles that Raz will have to face in order to complete his missions. Combat is handled through the use of special psi powers and melee attacks, as I previously mentioned, with there also being a special targeting system built in that can be used to highlight and select enemies, something which seems more geared to a console but still comes in handy when playing on a desktop computer nonetheless.

Moving on to deal with the elephant in the room, one can not review Psychonauts without going into some of the bugs. The original Linux release was barely playable, and the original version I played was still racked with bugs. The in-game interface did not properly update, the screen would go permanently blurry upon using the bacon or collecting a brain, the performance in some parts was frankly terrible, and many of the effects simply did not work. That being said, a lot more work has continued to be put into the game since then, and while the port still is not done, it has gotten a lot better. The water effects have been fixed, the interface problems have been sorted, and most of the performance issues resolved. Certain effects, such as in-game projectors, still do not work and the game still runs a little slow in places, but it is now at least fully playable and there is no reason not to believe more work will continue to be done on it in the future. There also still remains a key-binding issue that makes it so the game does not always save your configuration changes on first try, but a little persistence will eventually resolve this.

Not all of the problems seem to be specific to the port either. I have already related to you the frustration that the final Meat Circus levels can cause, but one particular part never seemed to work as advertised. One area involves jumping on and over a metal fire spiral, and the camera never seemed to move as it was supposed to. After quite a few attempts I did manage to complete it by balancing precariously on the rim of the metal fence and using my levitation ball to glide to where I needed to go. Looking for a solution online, I had already encountered quite a few other people complaining about that little problem, with most of them playing the game on other platforms. Such events do little to help what was already a much derided piece of level design.

Much of these complaints could have been avoided by a more liberal save system. The game still shows some conversion faults due to its console focused past, and one of them has to do with the save system. Saving one's progress does not save a person's exact position but rather informs the game about the player having reached a certain checkpoint with a certain set amount of points and inventory items. There is also no quicksave key in evidence, which would have really been a life saver during the game's final levels. The fact that the game frequently uses pre-rendered cutscenes rather than dynamic in-game ones also seems to be a bit of unfortunate baggage from its console past. The game's menu system is also rather cumbersome to navigate with a mouse and keyboard thanks to it being designed for a controller, and while the interactive parts do seem cool, they now seem a little out of place. Incidentally, through the menu one can also access Raz's journal which keeps track of such things as his game objectives, the memories he has collected, and how much points and collectible items he has.

The game can currently be purchased for Linux through Steam; DRM free versions were offered through both Humble Indie Bundle 5 (2012) and the Humble Double Fine Bundle (2013) and as a result can now also be purchased through both the Humble Store and the Ubuntu Software Centre. Double Fine has also expressed some interest in allowing the Linux version to be purchased through some other services, but has never actually committed to doing so as of the time of this writing. Since the games' initial release there have also always been several different rumours about a potential sequel, something which originally seemed hampered by the game's poor initial sales but now seems a lot more likely thanks to the game's recent rebirth. While nothing has been confirmed or agreed upon as of yet, it is definitely an idea to look out for in the years ahead.

Ultimately Psychonauts has to be viewed as a flawed masterpiece. It is undeniably a modern classic, but it has enough gameplay flaws, inconsistencies, and ever present bugs to prevent it from getting a full and proper endorsement. Its unique presentation, situations, characters, and setups do well to distinguish it from and even excel compared to its peers, but its flaws prevent it from being universally hailed as being better than the rest. That being said, it is a game I would most definitely recommend giving a play-through if for nothing else than to see just what can be accomplished when games are treated seriously as an artistic medium. It still has enough good ideas and skilled presentation to make it unparalleled in what it does right, and that is more than enough reason to give it a try.

Hamish Paul Wilson

July 16, 2013

May I ask who made it an Editors Pick? No, I was not arrogant enough to make it one myself. ;)I will never tell.

How to set, change and reset your SteamOS / Steam Deck desktop sudo password

How to set, change and reset your SteamOS / Steam Deck desktop sudo password How to set up Decky Loader on Steam Deck / SteamOS for easy plugins

How to set up Decky Loader on Steam Deck / SteamOS for easy plugins

See more from me