In the first of a two part opinion series, we will explore how the Penumbra games through a process of gradual evolution created a solid design template for later Frictional Games titles to follow.

CLICK HERE TO READ PART TWO

Author's Note: Being an editorial this piece is purely a reflection of the views of its writer, and in the vein of true artistic criticism, the opinions here merely reflect my own personal appreciation, or lack thereof, for the associated works in question. As such, they should not be taken as being either a condemnation or an expression of contempt for the actual living, breathing people behind these works. I should also stress that this article will contain numerous spoilers which may negatively affect people who have yet to play the games in question.

It feels strange to me that, even though I only started using Linux as my primary gaming platform relatively recently in the grand scheme of things, the fact that I made the jump all the way back in the ancient days of 2007 can make some of the newer adopters feel that I am one of the great old ones. That is certainly not the case, and I very much encourage people to read up on the full and proper history of our platform and its associated video games industry, something that actually stretches back at least twenty years or more. Still, considering the subject I am about to review, it seemed only appropriate to start things off on the right foot with a slightly dodgy H.P. Lovecraft reference.

The independent gaming market was still very much in its infancy 2007, with digital distribution still being on the fringe of acceptance, with most people still acquiring their games on retail disk. This of course meant that, other than a spattering of usually older game titles, the selection on Linux remained very much limited. Even then though we were still very much on the cusp of something great, as in the spring of that same year a small development studio in Sweden put out their first commercial product in the form of Penumbra: Overture (2007), the first instalment of their episodic Penumbra series. The game was remarkable enough simply for what it had to offer on its own merits, but what made it all the more surprising was that a Linux version of the game was put out within a mere two months of the original Windows release.

Overture also offered something that many people had already given up for dead at the time; a focus on pure survival horror with less of an emphasis on either heavy weaponry or all out bloodshed. As the Indie gaming boom increased in scale a whole raft of previously cast off game genres would find their way back to land of mainstream acceptability, and thanks to Frictional Games pure survival horror would be one of them. Strangely enough though Overture itself was not actually a pure survival horror experience in its own right; the main narrative that one can always attach to the Penumbra series is one of progression. While the main selling point of the game was its unique for the time take on object interaction from within the game world, it also featured in limited degrees some combat in the form of melee weapons which could be used to counter weaker enemies such as dogs and spiders.

The game itself made a great deal of noise that these things should be avoided if at all possible, and it did at least try to make using these weapons difficult, but once one got into the rhythm of things it was always far easier just to bash these annoying creatures on the head enough times, rather than have them get in the way of your puzzle solving. The fact that Overture could also be classed as an adventure game was yet another example of how it was trying to rehabilitate long forgotten game genres, even if it actually had a very modern way of doing so. As I mentioned previously, the Penumbra games were one of the first to allow for a more authentic way to interact with most of the physical objects in the game world, as through the use of the free software Newton Game Dynamics physics system objects could be picked up, dragged about, thrown around, and agitated through the use of specifically defined mouse gestures.

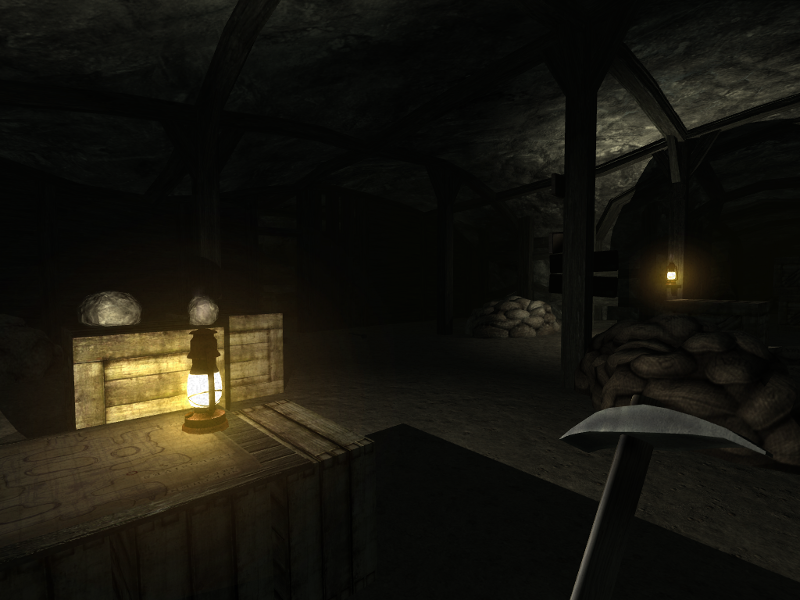

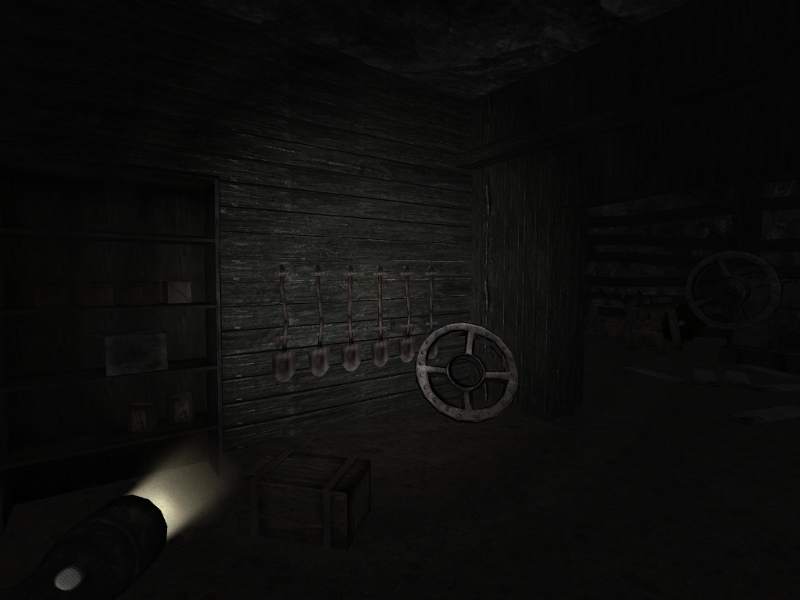

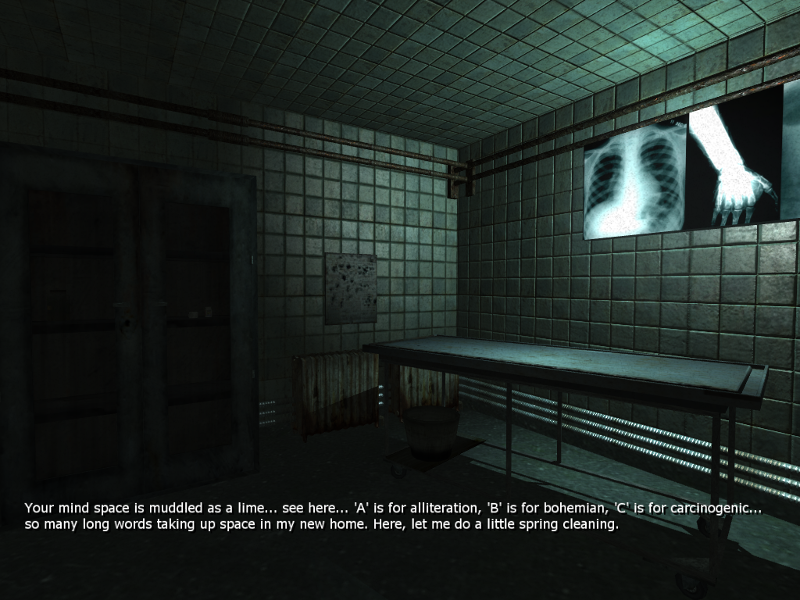

At a time when video game consoles were just starting to experiment with dodgy motion control sticks and other such measures, the fact that a tiny developer from Sweden had arrived at such an elegant solution using existing computer controls was nothing short of remarkable. The real appeal though, for me at least, was in the finer aspects of the game's crafting. From the environments to the characters, a lot of effort was put into making a convincing world, despite the obvious constraints placed on the game by the developer's budget. Overture takes place in an old abandoned mine in northern Greenland, and within the confines of this harrowing world a distinct narrative was spun from more than just the multitude of written notes hidden about the place. The thing which always strikes me about Overture, and indeed the entire Penumbra series as a whole, is the fidelity present in the environments, something which allows them to always strongly evoke a specific time or place.

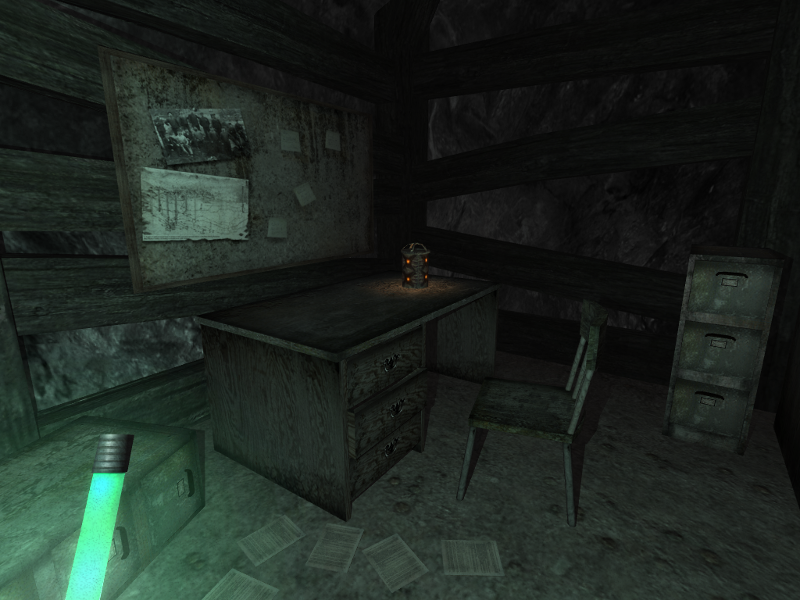

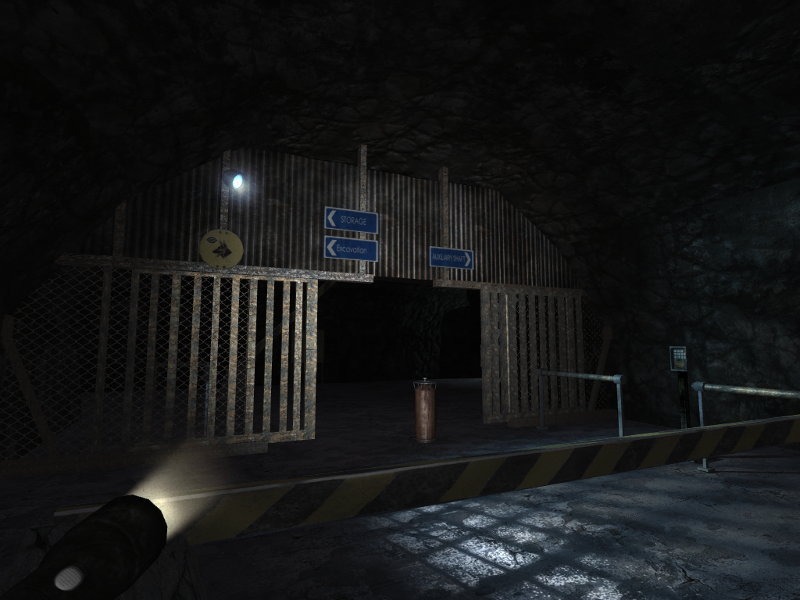

As one progresses through the mine one can see a history emerging merely from observing the construction of the walls, not to mention the tools, the equipment, and the mementos that the various miners have left behind. I am a strong believer that art should be made to best suit its particular medium, and given the fact that the main thing that sets gaming apart from its contemporaries is the interactive aspect, having a story told simply from the exploration and interaction with the game world is a real pleasure to behold. The oldest part of mine dates back to the early 1930's and the Second World War, and later on in the game the player reaches newer additions that were built in the early 1970's. Everything from the lights, to the equipment, to the feeling imparted by the construction of the rooms present in each particular section so successfully manage to correspond with my own interactions with similar objects from those decades as to send a reverential chill down my spine whenever I see them.

All of this can add beautifully to a horror game, as there is always going to be something innately creepy about the past, especially the recent past, largely because it functions something like a fun-house mirror. It serves to show us a strange vision of our own lives and societies, exhibiting a world that is still so much like our own and yet at the same time still so uncomfortably dissimilar as to seem almost alien to the modern observer. It is all quite disconcerting, and it definitely shows what can be done when one realizes that creating an effective feeling of horror can depend on more than just elaborate displays of blood and gore, despite how welcome these can be in many other games and contexts. It also shows that gaming does not necessarily need to resort to the same trick and traps as other mediums to impart the same emotional effects.

If that were not enough, the game also had another ace up its sleeve in the form of Tom Jubert, a professional game writer which has in recent years been involved in a number of critically acclaimed titles for a variety of platforms; Linux gamers might also recognize him for his work on such games as FTL: Faster Than Light (2012) and The Swapper (2013). The basic plot of Penumbra had already been basically established by the time that the initial technological demonstration was first released in 2006; the game's protagonist Philip receives a letter from his dead father urging him to destroy the last trace of his work in an unidentified location in northern Greenland. Unable to contain his curiosity, Philip instead endeavours to uncover his father's buried secrets, only to discover that some things really are better left buried.

Although having the somewhat novel aspect of being delivered in an epistolary format, the main plot of the game is actually far from extraordinary; it is for the most part the same Lovecraftian fare that gaming has been obsessed with since the dawn of the medium. In fact, the name of the protagonist's father as well as the player character himself are actually named as deliberate homages to the infamous American horror author, with them boasting the handles of Howard and Philip respectively. Instead, the real draw of the story comes not from the background plot but from the characters, an element of the game that Tom Jubert himself actually had a huge amount to do with. Once again the game's limited budget comes into play, and while little is actually seen of Jubert's various creations, their presence is actually felt all the more because of it.

Overture features one character which is only known from a collection of sound effects, some notes, several wood engravings, blood trails, and a severed tongue. Once again exploration and interaction are the game's watchword, and one has the liberty to discover as much or as little about the character as they choose. Any commentary on Penumbra would of course also be remiss without a few words about Red. Played to perfection by voice actor Mike Hillard, Tom "Red" Redwood is a trapped miner driven to the edge of sanity by being left on his own for decades, with nothing more than some books and his own mental imaginings for company. The result is a man with very little idea of what he is truly saying, resulting in some truly unnerving while at the same time highly amusing phrasings.

Once again the player's interaction with the character is limited only to hearing the man's voice over the radio, at least until the game's affecting final moments. The end result of this is that Red can still assert his presence without getting in the way of the player's own sense of isolation and loneliness, an integral part to any survival horror game which many of its busier contemporaries often seem to forget. Through a variety of written notes, more of the mine's former inhabitants are also revealed to the player, and while in Overture these may have been overused to the point of breaking credulity sometimes, they do at least help provide some context to the well crafted worlds that Phillip finds himself in while journeying in search of traces of his long lost father and his associated works.

The next instalment, Penumbra: Black Plague (2008), significantly expanded the amount and range of characters encountered directly in the game. Philip is given a new voice in his ear, or rather mind, in the form of Clarence, a malevolent personality that forms after he contracts the same virus that has overwhelmed the rest of The Shelter, an underground facility adjacent to the mine which is presented as Philip's ultimate objective, as it is where his father was. More overtly aggressive and evil than Red, the new personality never the less seems to have the same penchant for interesting wordplay, with an added interest in twisted cultural metaphors. Phillip also encounters several surviving members of The Shelter's staff, including a less than sane medical doctor, a gruff societal acolyte, and the unnervingly calm intonations of one Amabel Swanson, who I shall return to later.

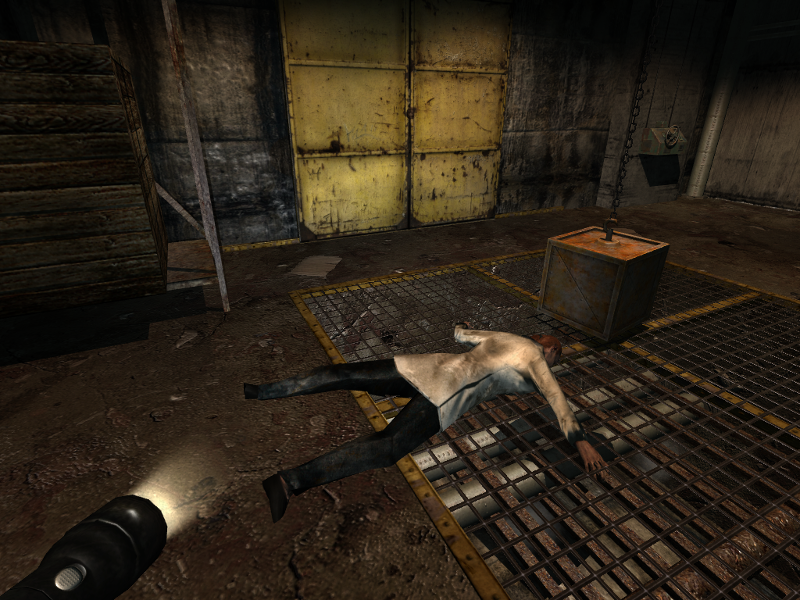

The Shelter itself also proved to provide a wonderful new environment for the player to explore, and once again managed to present a self-contained world that is wonderfully steeped in its own particular time and place, which in this case was the start of the new millennium. One puzzle even has the player having to reconfigure a period computer system, bringing back fond memories of my much younger self playing around with similar machines now well over a decade ago. In addition, Black Plague also does away with the limited combat seen in Overture, dropping dogs and spiders in favour of enemies old and new that must be avoided purely by stealth, traps, or through progression to the next area. This helped to refine the game experience hugely. The fact that Black Plague also represented the finale to a series initially intended as a trilogy also meant that the general plotting became tighter and faster paced, which in the end was for the better as it created a much more focused and concise story.

Returning back to the subject of the game's characters, it can also be said that Penumbra as a whole can be seen as having a linking thread of death, and while this is far from from uncommon in either gaming or the horror genre, the way that the series handles it was nevertheless still unique and all together rather unexpected. While it might seem strange to gloss over Red's eventual end as it was the first instance of this mechanic, far more striking for me was the death of Amabel. Now, as one can probably tell simply from reading this, I am rather pedantic when it comes to my gaming, so I rarely enter a game without a good grasp of what it is I am going to be dealing with. Because of this, I already knew most of the plot points that I would be presented with as I was playing Penumbra, and I was not expecting to be all that surprised by them.

The first time I played Black Plague I was in the company of several of my brothers who were watching me play and offering suggestions as I made my way through. I know that Frictional Games themselves always recommend playing the games alone in a darkened room with headphones on, but as the player I am of course allowed to grant myself certain liberties when it comes to how I choose to engage with a game. After having worked through most of the episode, we were now finally getting ready to meet up with the woman behind the elusive voice which had been ever so politely leading us on for most of the chapter, as opposed to Clarence, who had been trying his best to force us off for most of it and failing badly, albeit in his own amusingly wicked fashion. We entered Dr. Swanson's laboratory and, after a little more messing around, proceeded to the back room.

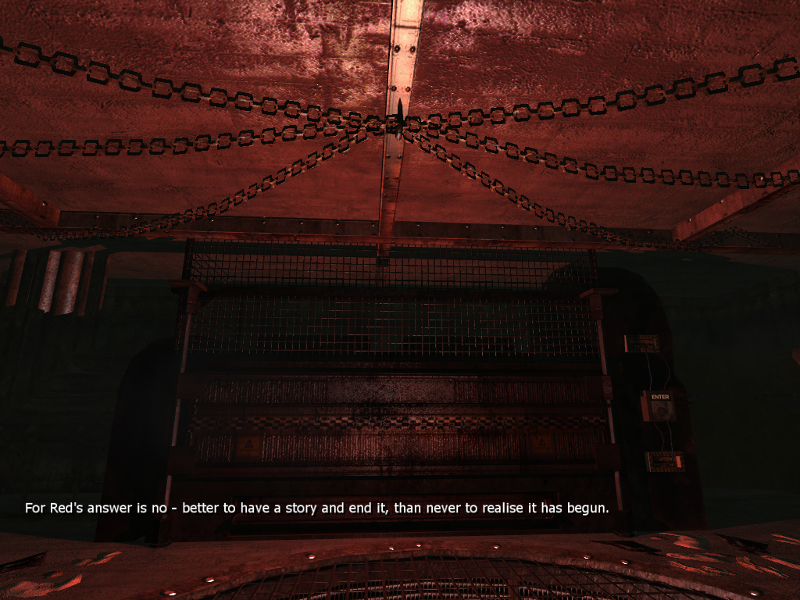

There was no sign of the lady which had been communicating to us through all of those computer terminals. Then one of the infected suddenly burst in instead. Inside the room there was a box suspended in the air by a chain, with a control wheel attached to a wall that would both tighten and slacken it. There was nothing else left for us to do. Tricking the creature to wander its way under it, I quickly spun the control wheel, unleashing the full weight of the crate on top of the creature's head. Or so I had thought, my attention of course having been diverted away to the wheel control. A piercing scream assaulted the room. A question was then voiced by my compatriots who were watching the spectacle unfold with me: “What's that scream?” That is when I turned, and that is when I saw it.

The point of the matter is, I knew full well that this was coming. I already knew that Amabel was going to die and that it would be at Philip's hands thanks to Clarence's mental tricks. I had already been versed in the plot well enough to have learned this fact. Even then, the game had still managed to surprise me. It had exceeded my expectations. Normally such an event would have been beyond the hand's of the player, even if it was an action ordained to have been undertaken by the protagonist, or at the very least been presented to you with a very heavy amount of scripting. Something about how this was done was different though. While the fact remains that her death was indeed a forced game path that one could still not avoid, something about it seemed so deeply personal as to make one really believe that it was their own actions that had made this terrible mistake.

Several factors were at play here. One was the absolutely outstanding casting present in the series, which is uniform and unbroken throughout with the possible exception of the rather humdrum performance given by Tom Jubert himself as Philip reading over his letter at the start of the first episode. I have already heaped deserved praise on Mike Hillard's performance as Red, but the other cast members were just as talented. Emma Adam gave a somewhat challenging performance as Amabel, delivering every single line in a strangely calm and detached fashion that perfectly suited the character and strangely endeared one to her in a fashion that is rather hard to comprehend. Robert Pike Daniel's over the top acting as Clarence also benefited the game greatly, giving it all the twisted energy it needed to carry the narrative forward through all of its many dark moments. They all gave performances that provided proper emphasis to the events taking place on the screen.

Probably the strongest reason why this particular scene worked so well though was once again due to the writing. We had already experienced the death of Red under similar circumstances after all, making it so much thought was needed in order to make the second event still have the same or even greater weight than the first. Tom Jubert on his blog put out a detailed character postmortem of Amabel that I strongly agree with, which fleshes out quite nicely how the event was put together and why it was needed. One point which he mentions which might not be fully understood is the relation she has to Clarence and the importance she plays in developing that character arc. You see, there is actually a problem with the character as he is portrayed in the games. Maybe not one that would matter to Phillip himself, but for the player it is amply evident that Clarence is in fact likeable.

Sure, he is undeniably evil, hostile, and in your face but he is also undeniably cool and interesting. It is the curse of having an entertaining villain that you still have to make him or her less appealing than your hero, and we badly needed more reasons to hate Clarence other than him making things a little harder for us on occasion. Much of the game was already doing that for us anyway. We needed to have this other character that we also liked, that we wanted to save, for Clarence to demonstrate to us that he was still a palpable threat and an evil that must be neutralized. Any game that can work such a powerful bit of character work deserves comment, but the fact that Black Plague did it on the back of an already similar and successful scene in Overture truly takes the cake.

Even when the main plot was over the characters still remained front and centre. In the much underrated expansion to Black Plague entitled Penumbra: Requiem (2008), most of the action seemingly takes place inside Philip's head, and building on this metaphysical bent, the game's plot is never strictly defined and is as such very much open to interpretation. The most enjoyable aspect of Requiem though is the fact that it reunites us with most of our old friends from the previous parts, only this time skewed through the processes of Philip's own mental perceptions. Eloff Carpenter the Archaic acolyte, Richard Emminis the medical doctor, Red the insane miner, and of course the Shelter announcer all make an appearance, building on their characters and once again making them appear larger than life. Red in particular is in fine form, spouting some truly wonderful quips, although Emminis is also not short of many intriguing lines of wisdom either.

While Requiem took what many people thought was a step back in its decision not to include any monster encounters, it also completely abandoned the use of purely inventory puzzles and instead offered up brain teasers that were almost entirely based on physical object interaction, resulting in a much smoother and innovative gameplay experience than what was offered in previous episodes. I managed to play through the whole thing in one memorable evening, and I credit this particular puzzle paradigm for much of that success, even with the episode's admittedly shorter playing time. It was not until the spring of 2010 that I finally got around to trying out all of the Penumbra games, playing them all in one glorious protracted stretch. What I was left with was the impression that Frictional Games held in their hands the general blueprint for a truly exceptional followup.

Assuming the developers could manage to take all of the best ideas from their previous games, such as the presentation and enemy encounters of Black Plague, the puzzles of Requiem, the excellent character work of Tom Jubert, as well as the general atmosphere and environmental fidelity that existed throughout, I was sure that gaming as a genre could be graced with a title that could take it to new never before seen heights. As luck would have it, in the fall of that same year Frictional's next product was unleashed onto the world's unready masses. It did not take long for it to attain vast and widespread critical acclaim, far outshining its predecessors in terms of popularity, purchasers, and general renown. Yet there was still something missing that only I seemed to be able to see; it did not follow the design script that Penumbra had provided for it.

In the next instalment, I will offer up my own personal conviction that the Amnesia games do not actually live up to the full potential demonstrated by their predecessors.

I think the root problem with these games with no/not many weapons is that I don't stick with them long enough to really get into the story, which is what makes them good. I have read nothing but praise for Penumbra over the years so I promise to REALLY try to give them a go when I do. I don't know if there is much hope for me and Amnesia though.. I've tried a couple of times and I just can't do it. I get bored too quickly.

I love the Penumbra games to bits. I did play them in a darkened room with headphones, and, yeah, that was an unique experience.

And while I do think it's weaker, I still like The Dark Descent. A Machine for Pigs kinda didn't really grip me, I'm saddened to say. I played a few hours and didn't return as of yet. It feels a bit too...scripted, too much like a fairground haunted house to me.

About SOMA: I'm a bit disappointed that it is going to be another one in that style. After those real-life teasers, I kinda hoped for an FMV adventure, like Tex Murphy or Ripper. I want it to explore the themes it invoked in the teaser: how the mind works, how you define a personality, if you can copy a mind; all those transhumanism themes. And I think you can do that better in an adventure game than a survival horror one.

And while I do think it's weaker, I still like The Dark Descent. A Machine for Pigs kinda didn't really grip me, I'm saddened to say.

Oh, don't get me wrong, I do still like Amnesia as well, and can even say a few nice things about Piggies... but then I should save any elaboration on that front for the next article. ;)

Excellent article. Saved to my Documents folder.

TWIMC: Valve - RED - From Software - 4A - Frictional

SOMA Steam dayONE FTW!

Interesting article. :)

A Machine for Pigs kinda didn't really grip me, I'm saddened to say. I played a few hours and didn't return as of yet.

Nope.

Frictional Games --> Amnesia The Dark Descent

The Chinese Room --> Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs

Frictional was still the publisher for A Machine For Pigs and had a supervisory role on it, so they can not completely wash their hands of it, if you would agree to the term..Yep. Though I want to know how much supervisory on it.

I could say easily that clarence is one of my favorites chars in games!

"Im taking u with me!"...monkey!

How to set, change and reset your SteamOS / Steam Deck desktop sudo password

How to set, change and reset your SteamOS / Steam Deck desktop sudo password How to set up Decky Loader on Steam Deck / SteamOS for easy plugins

How to set up Decky Loader on Steam Deck / SteamOS for easy plugins

See more from me