Taking the red pill from the white rabbit

“It’ll be like Star Wars and The Matrix are making a baby, but more like Alice in Wonderland!” I say to my brother Richi.

We are sitting outside a German cafe, enjoying the last warm days of 2015, imagining our video game project. We wanted something like Zelda on the Super Nintendo but more futuristic. And with pixels — many, many pixels.

When we left the cafe a few hours later, that conversation felt like a story I could carry around forever, but never dare turn into reality. Better to stick with the blue pill.

Back home, Richi was booting up his Ubuntu machine. Precise, reliable, elegant, it was the lightsaber of operating-systems. An 18 year old brick that has served as his stable companion since the days of Hoary Hedgehog.

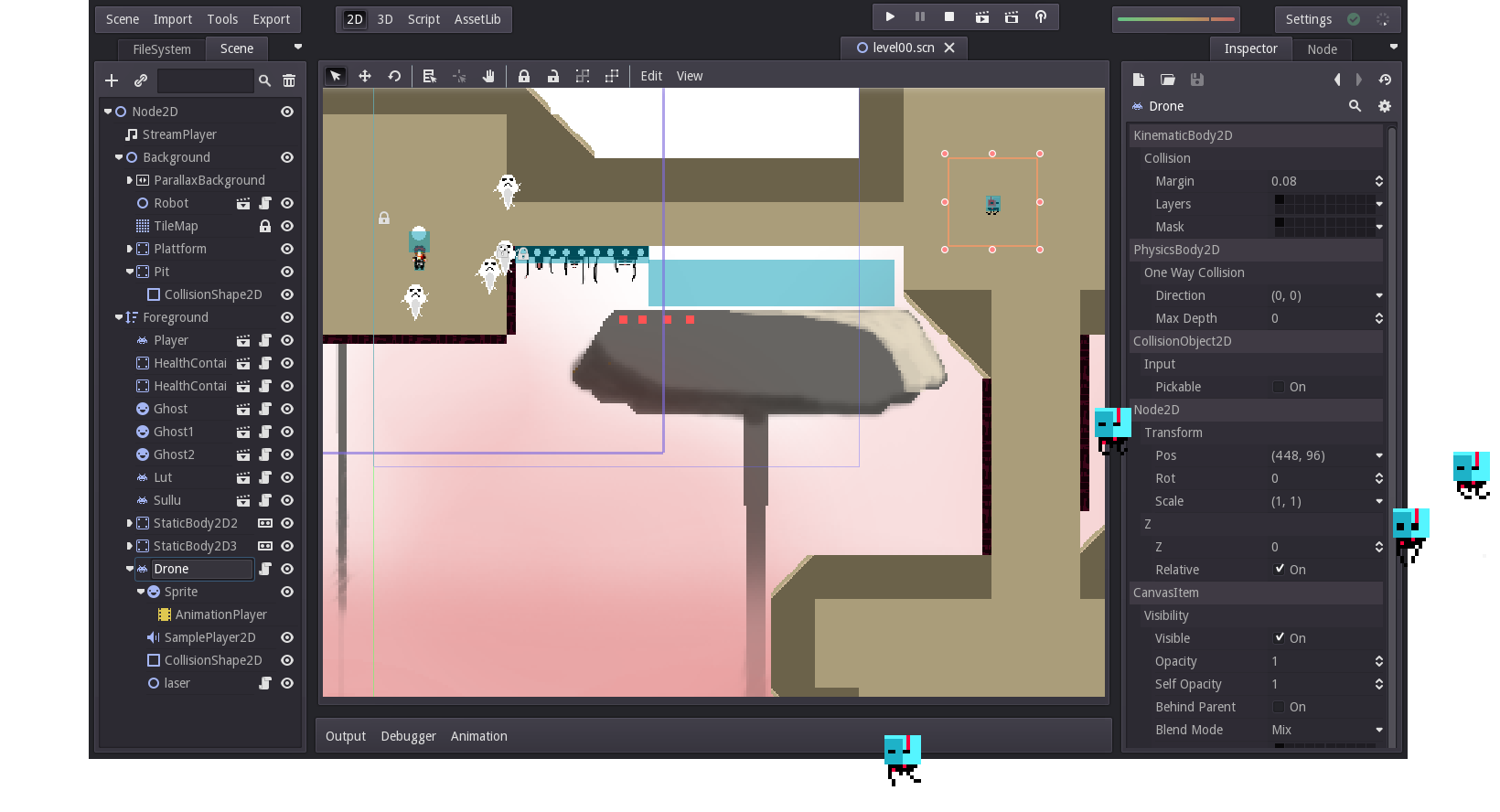

Researching game engines, Richi finds a few that are capable of running and exporting reliable code to Linux. Eventually he stumbles upon Godot. The engine feels fresh and thrives by embedding itself nicely into every open source stack. The python-like scripting language and node-tree-architecture certainly helps sell the engine to a complete beginner.

Two weeks later Richi was able to make a black dot is run across his screen, magically directed by pressing W, A, S or D on his keyboard.

“Godot is really great for 2D games,” Richi tells me, nudging the black dot back and forth. “So, you want to head deeper down the rabbit hole?”

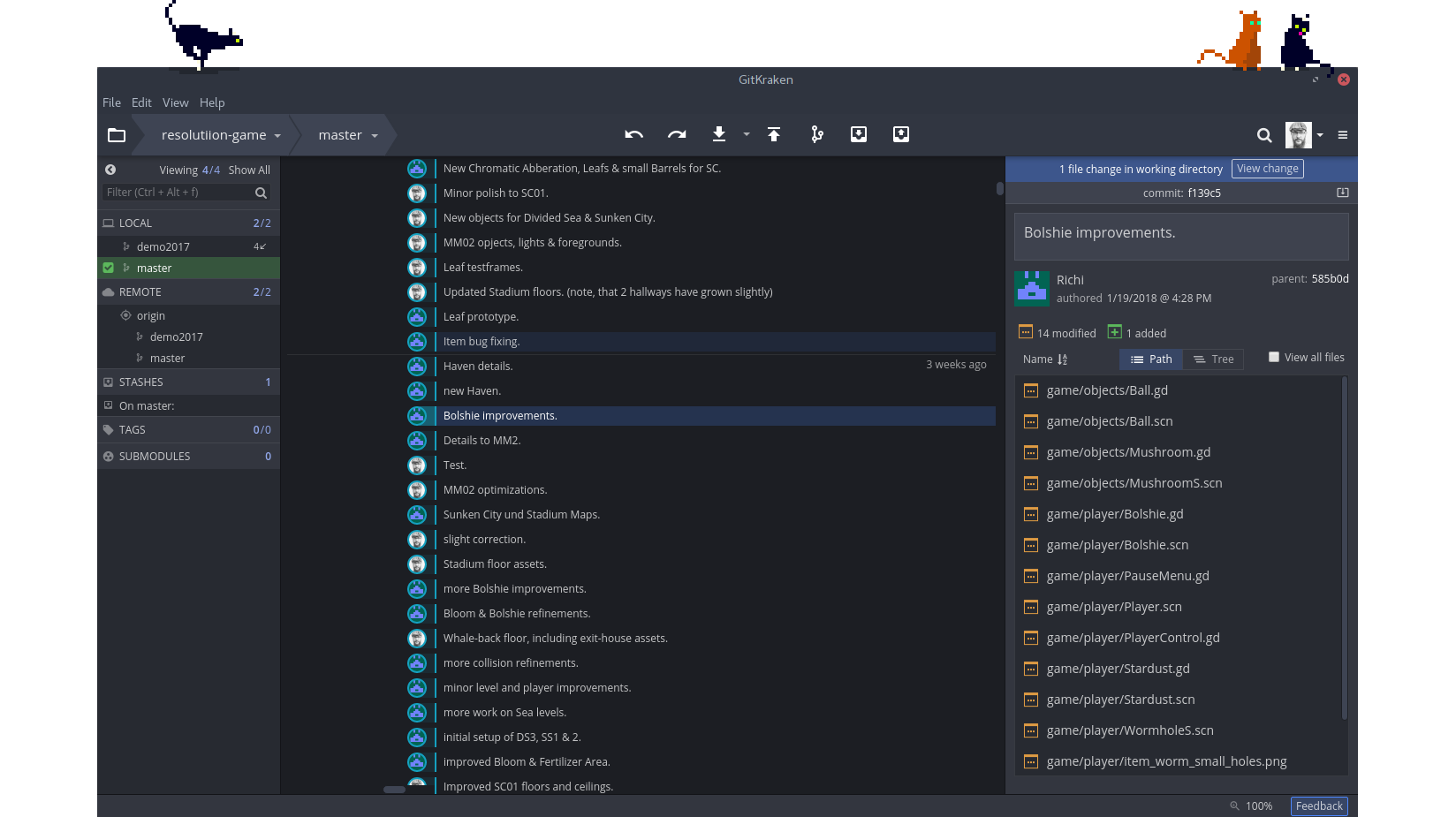

It takes eight more weeks to set up a Gitlab-server for collaboration. Pull, commit, push. Through the dark command line, we battled endless merge-conflicts until GitKraken finally rescued us from that fugue by helping us understand versioning and the determining logic.

Our first commit reads: “Resolutiion.”

Never send a machine to do a Jedi’s job

With the engine running and some core mechanics in place, we turn towards the game as a layered experience:

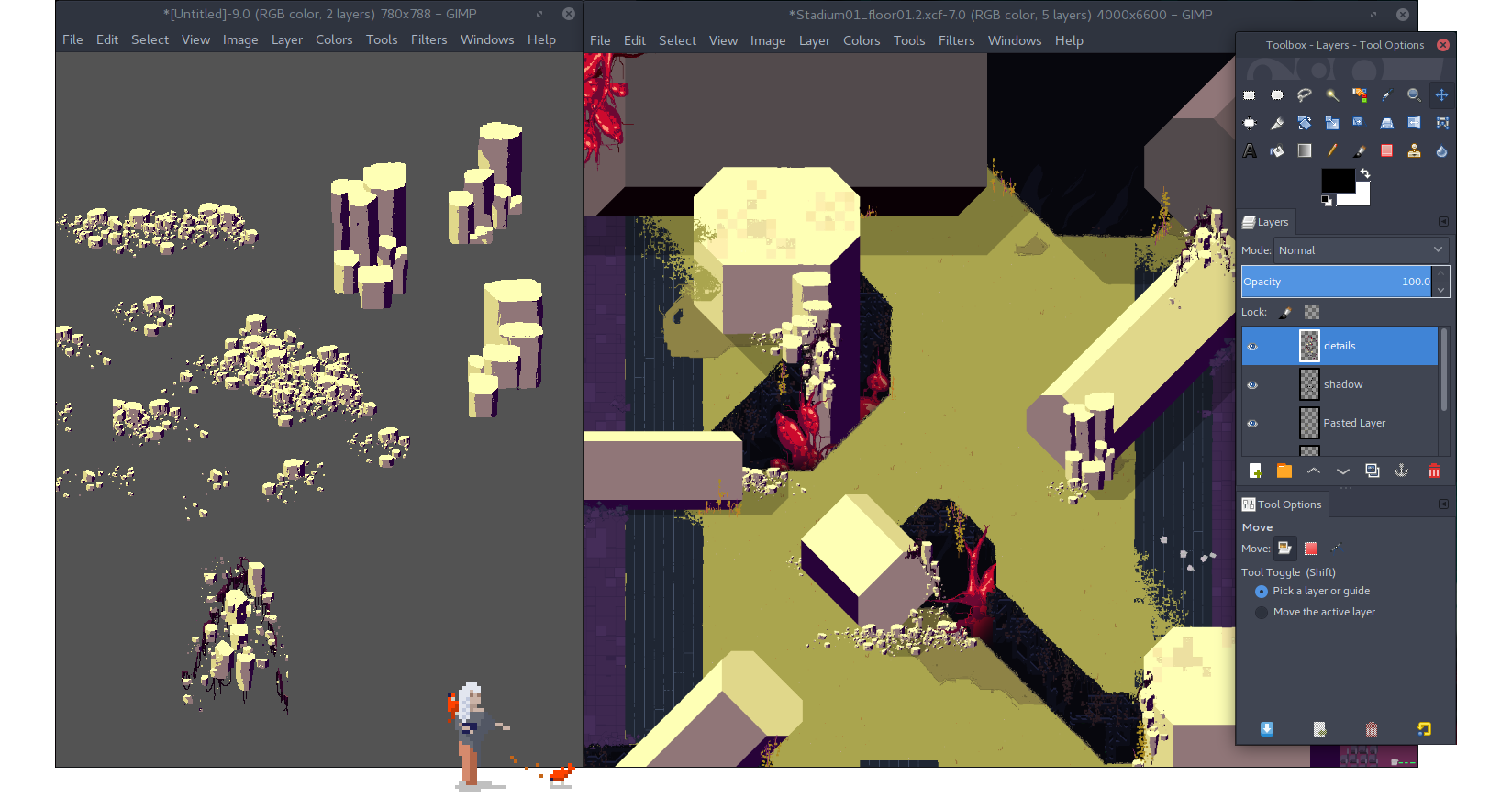

“Putting together some graphics with Gimp is easy, right? We just need a background to walk on, a couple of character-frames, maybe one or two attacks. A little background, parallax layers if possible. And destructibles — those are always fun. And items. Furniture. Enemies. More, more, more …”

Agent Smith is taking over the Matrix.

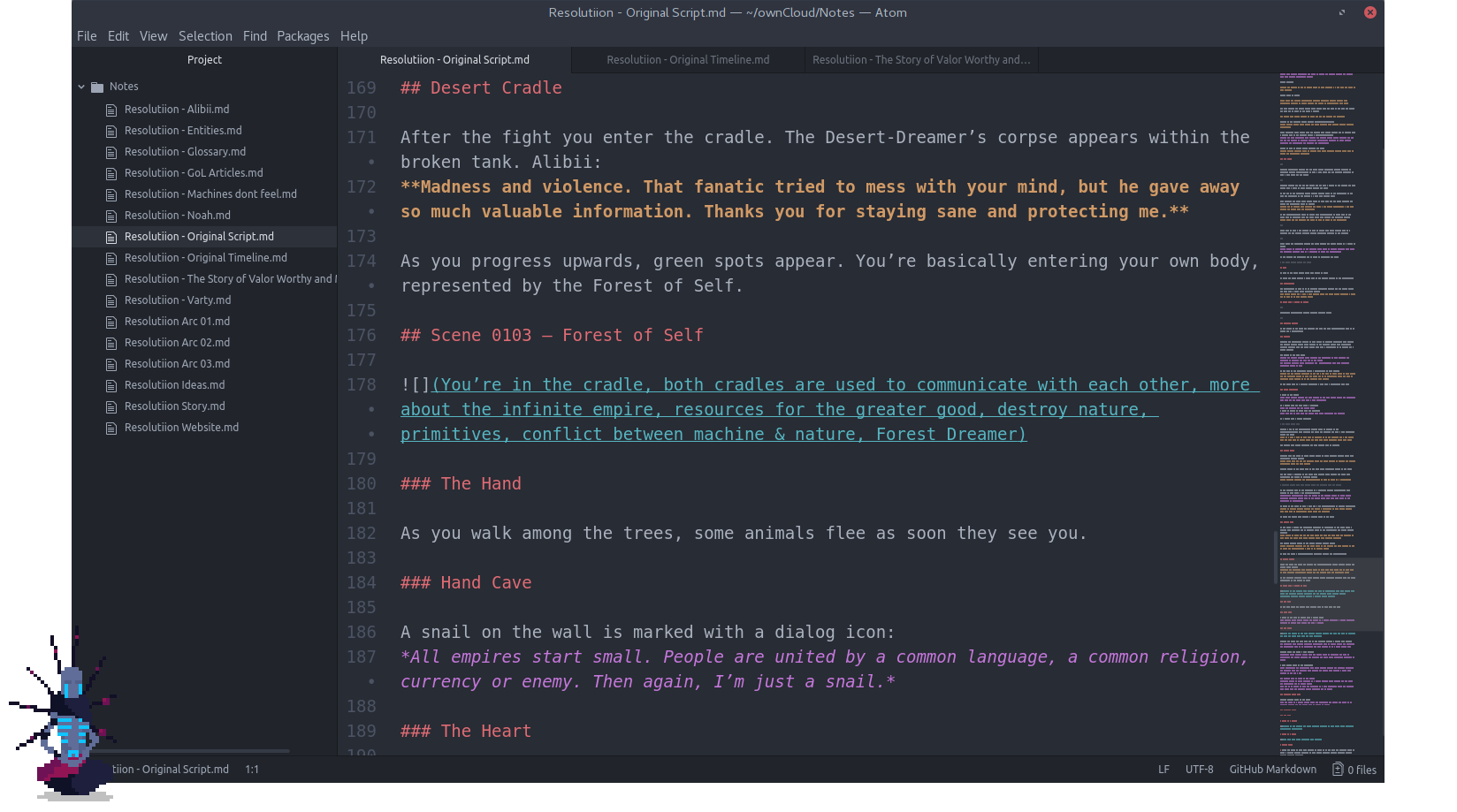

Back home from the inspiring coffee-session in 2015, I'm struggling. With plenty of graphic-design-experience on Linux, I realize that designing a video-game is completely different than the client work I'm familiar with. What’s the point of this protagonist? Why is it motivated to kill all of these enemies? What’s the story? What about politics, economics, linguistics?

As these questions pile up, I start my Antergos laptop with Atom in Zen-mode. This bare-bones software-stack has helped me work through some creative-blocks in the past. Pushing aside the noise of a million unanswered questions, I remind myself: always start with the writing.

I've always been interested in stories about power — the struggle of the powerless to become powerful, and the powerful to stay that way. Skywalker Vs Vader. Anderson Vs Smith. Man Vs Machine.

Resolutiion is about that struggle between man and machine, though one hundred years from now, its lines are blurred: transhumanism and artificial intelligence have extended inequality. The Infinite Empire has reached global control of economy and thought. Resistance comes through small tribes, that pray to great mysterious machines — the Cradles. Within, powerful beings are born, creating a seperate network of the mind, outside the reach of the Empire.

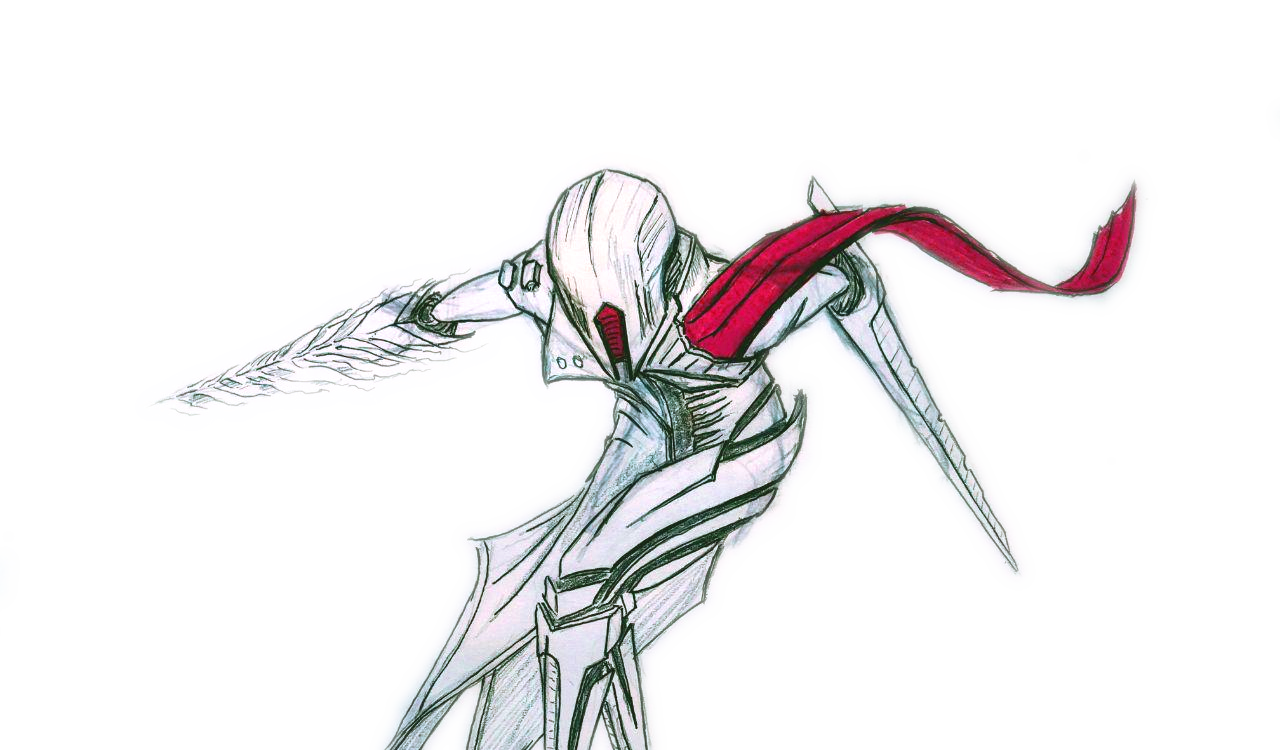

The hero appears as the executioner for the empire: not your proud Jedi cloaked with a noble cause, but a black marionette of flesh and death, ready to slay the false gods.

What good is a tea when you are unable to speak?

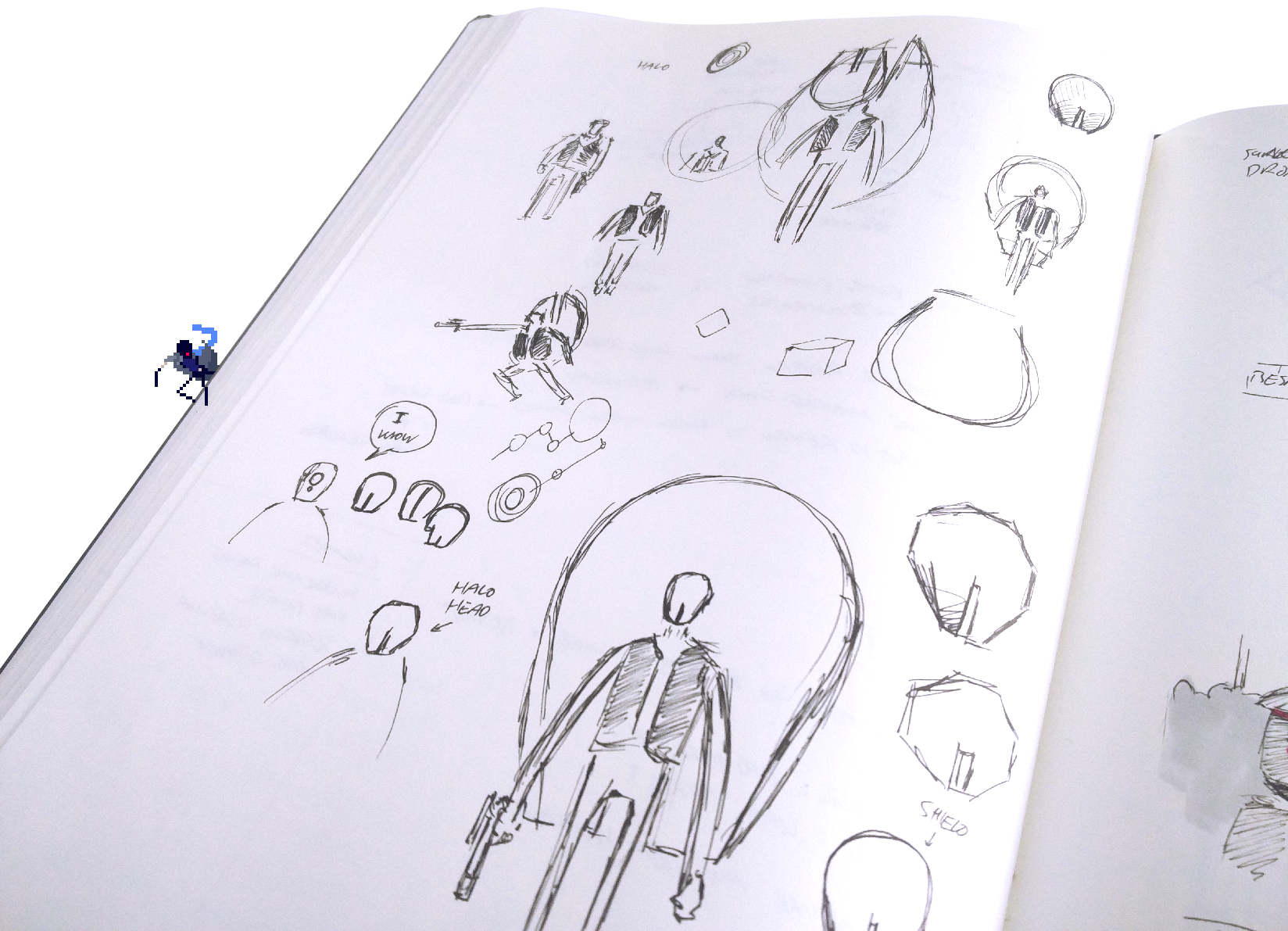

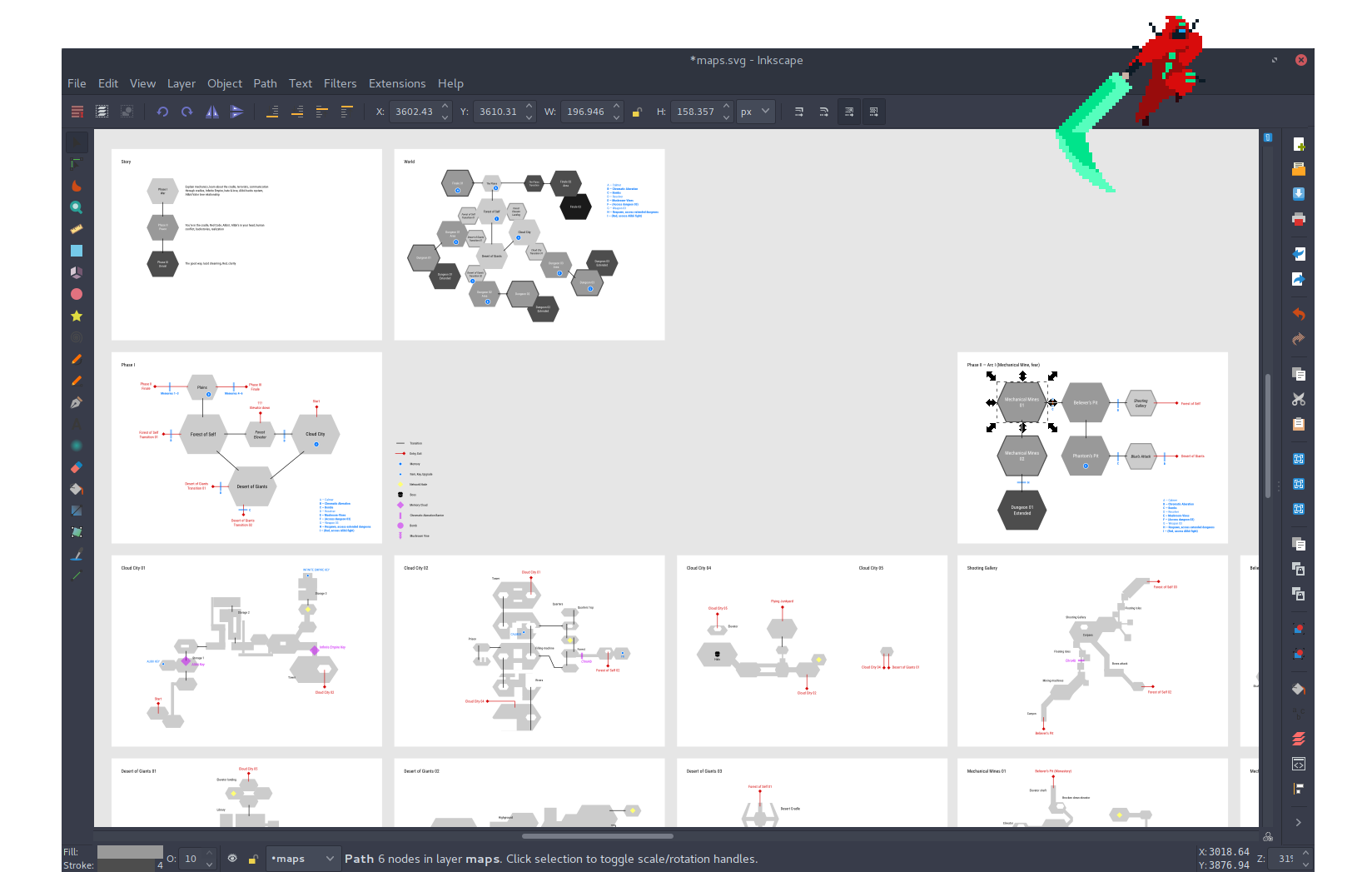

Richi and I push ideas back and forth like Solo and Chewbacca arguing until language becomes an overwhelming mess. At some point we realized we needed a visual system to move our concept forward.

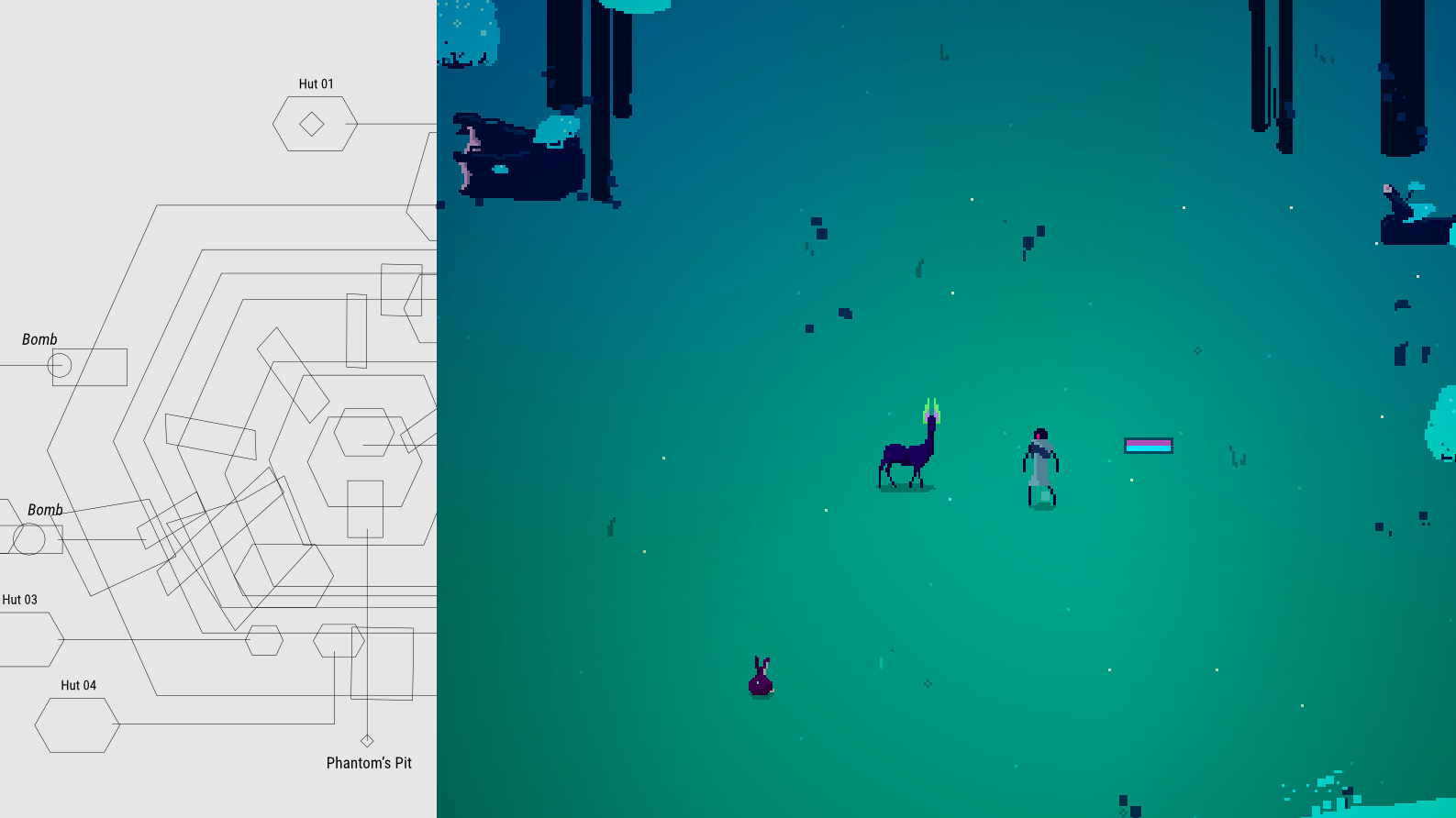

I’ve been using Inskscape since it was still called Sodipodi. I start by drawing a series of hexagons titled “Cloud City”, “Divided Sea” or “The Plains” that represent a level or scenario of the story. Then each level gets refined into a set of connected maps. After just 2 days, we were able to establish a visual understanding of the whole game and its critical path through plenty gray boxes on white paper.

In classic Zelda-style, we battle our way through the Desert of Giants, making use of claws, guns and the Chromatic Aberration. Fights are in real-time, fast and tactical. Interrupting our crusade, a flickering entity appears: “Your advance corrupts the Red Code. The damage is done, but you can stop here.”

We should probably kill it, right?

From here on out we're down to grinding assets. Gimp does a great job of pushing pixels, scaling, and the occasional layer-effect to shape our world. Sword & Sorcery and Hyper Light Drifter have shown how a modern pixel-aesthetics can carry the nostalgia of the 90s, without feeling like a blast from the past.

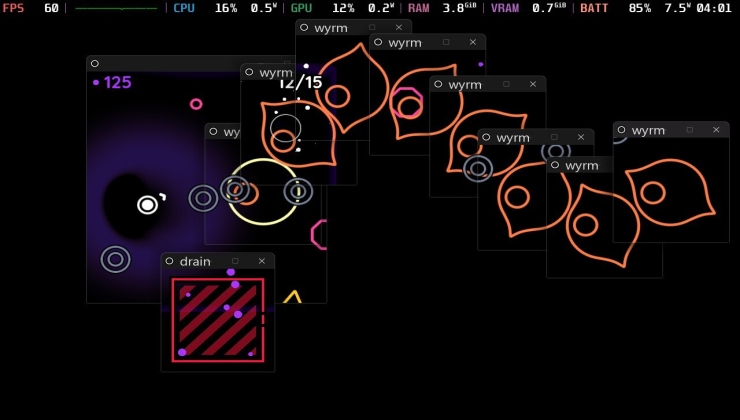

Every layer of detail gets chopped into sprite-sheets that make their way into Godot as backgrounds, objects, destructibles or enemies.

Since Gimp lacks a solid animation-component, Aseprite helps us to draw decent key-frames for every creature’s movements, attacks, or dying animations.

We’re all mad here. Im mad. You’re mad.

Months pass by writing characters, painting landscapes, coding puzzles and putting it all together. There are no randomized levels, loot-boxes or other gimmicks — just straightforward gameplay about a futuristic soldier, exploring an interconnected world, uncovering a layered story.

“Our network grows underground like a fungus; an infernal machine. When it reaches the surface it will erupt, drowning the old world in a cloud of life and possibility.”

–Green

Working with Linux came naturally to us. Surfing the web with Windows in 2005 was like running the gauntlet. Gnome had the Mac OS minimalism that every student wanted but few could afford. And then there was the idealism and free spirit of the FOSS community — just by using Linux, we felt like changing the world.

Driven by their respective communities, software evolves and we grow as artists. The game’s project-folder currently counts 1,527 files, all done within open-source environments. We’re certainly not the first on this path, and giving back to those fantastic tools by showing the world what they can do is the least we can do.

Today, we’re creating our own world.

Richi and Günther Beyer from Germany are developing their first video game. Inspired by early Zelda and fueled by the do-it-yourself spirit of the open-source movement, Resolutiion will ship in 2019, with plenty of pixels, cats and the mystery of the Cradles. Subscribe to our newsletter or tag along at Twitter.

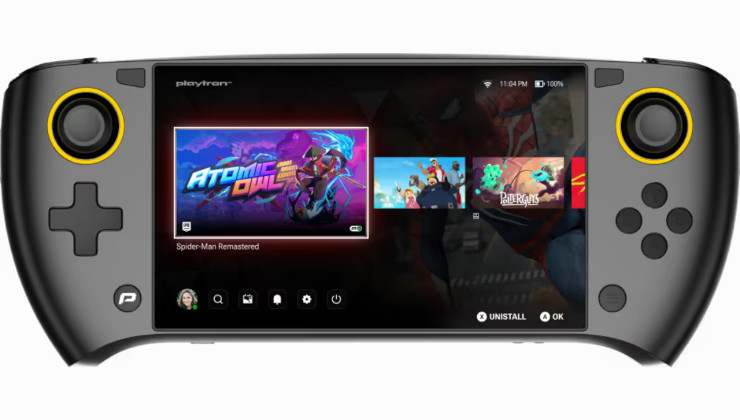

How to set, change and reset your SteamOS / Steam Deck desktop sudo password

How to set, change and reset your SteamOS / Steam Deck desktop sudo password How to set up Decky Loader on Steam Deck / SteamOS for easy plugins

How to set up Decky Loader on Steam Deck / SteamOS for easy plugins

I love this.

Absolutely amazing to hear a story about a cool game being made on Linux, via Godot. Insta-buy when available.

There's a lot of Zelda mentions, but this sounds like it's a heck of a lot darker. And more challenging. Hopefully it doesn't go too far in either direction that it stops being as accessible as those classic games.

You are on my watchlist... in the good sense of course!

I have to admit I am tempted to revive it and do a full linux development process and release. Software solutions available today are an incredible improvement over the tools we had 10 years ago.

Spoiler, click me

Last edited by Colombo on 1 Mar 2018 at 4:13 am UTC

*Off and on for around a decade, recently revived again by the surge in LTTP Randomizer playthroughs on YouTube reminding me it's been a couple years since I last thought about it.

Good PR.